As environmental and social challenges such as climate change, biodiversity loss, and resource security risks grow increasingly complex and urgent, more countries around the world are accelerating their transition toward a circular economy. In Japan as well, there is a rising expectation that startups will play a key role in driving this transformation. Responding to this momentum, Harch Inc., operator of the circular economy media platform “Circular Economy Hub (in Japanese),” launched the”CIRCULAR STARTUP TOKYO” program in April 2024 in collaboration with the Tokyo Metropolitan Government. This startup support initiative is dedicated to nurturing businesses in the circular economy space.

However, as attention toward the circular economy spreads across industries and policymaking spheres, there is growing concern that the term is gaining traction without a clearly shared vision of the “desirable futures” we hope to build. For startups and companies aiming to create impactful innovation, it is crucial to first articulate such a vision and then build strategies rooted in it.

To explore these questions, CIRCULAR STARTUP TOKYO hosted a special public academic session titled “Imagining Circular Futures: Transitioning to a Circular Future through Design, Technology, and Lifestyle.” The event featured three guest speakers—researchers and practitioners active in Japan’s circular economy and circular design fields, all of whom serve as academic advisors to the program. Together, they examined the notion of a circular future through three lenses—design, technology, and lifestyle—while offering critical reflections on the concept of circularity itself.

The session addressed the core questions: How can we envision a better future? And what actions must we take to realize it? Below are highlights from the speakers’ research, practices, and panel discussion.

Special Guest Speakers / Panelists

Daijirō Mizuno (Professor, Institute of Liberal Arts and Sciences, Kyoto Institute of Technology)

Born in Tokyo in 1979. Completed his doctoral degree in fashion design at the Royal College of Art in 2008. Earned a Ph.D. in fashion design. He joined Keio University in 2012, became an associate professor in 2015, and has worked on various projects exploring the critical relationship between design and society. Since 2019, he has served as a special-appointed professor at Kyoto Institute of Technology’s KYOTO Design Lab and, since 2022, as a professor at the Institute of Liberal Arts and Sciences. He also holds a concurrent appointment as a special invited professor at the Keio University Graduate School of Media and Governance.

Born in Tokyo in 1979. Completed his doctoral degree in fashion design at the Royal College of Art in 2008. Earned a Ph.D. in fashion design. He joined Keio University in 2012, became an associate professor in 2015, and has worked on various projects exploring the critical relationship between design and society. Since 2019, he has served as a special-appointed professor at Kyoto Institute of Technology’s KYOTO Design Lab and, since 2022, as a professor at the Institute of Liberal Arts and Sciences. He also holds a concurrent appointment as a special invited professor at the Keio University Graduate School of Media and Governance.

Hiroya Tanaka (Professor, Faculty of Environment and Information Studies, Keio University / Director, Environment Design and Digital Manufacturing Center)

Tanaka holds degrees from Kyoto University’s Faculty of Integrated Human Studies and Graduate School of Human and Environmental Studies, as well as a Ph.D. in engineering from the University of Tokyo. He began his academic career as a lecturer at Keio University SFC in 2005 and became a full professor in 2016. In 2010, he was a visiting scholar at MIT’s Department of Architecture. He has led national-level research projects, including MEXT’s COI program (2013–2021) on connecting digital fabrication with creativity, and currently serves as project leader for COI-NEXT’s initiative on a “Symbiotic Upcycling Society” built on respect and collaboration.

Tanaka holds degrees from Kyoto University’s Faculty of Integrated Human Studies and Graduate School of Human and Environmental Studies, as well as a Ph.D. in engineering from the University of Tokyo. He began his academic career as a lecturer at Keio University SFC in 2005 and became a full professor in 2016. In 2010, he was a visiting scholar at MIT’s Department of Architecture. He has led national-level research projects, including MEXT’s COI program (2013–2021) on connecting digital fabrication with creativity, and currently serves as project leader for COI-NEXT’s initiative on a “Symbiotic Upcycling Society” built on respect and collaboration.

Ikuho Kochi (Associate Professor, Institute of Transdisciplinary Sciences, Kanazawa University)

Kochi holds a master’s degree in environmental science from Duke University and a Ph.D. in economics from Georgia State University. Her expertise lies in environmental economics, educational engineering, and cognitive science. Her research focuses on transforming values, awareness, and behavior to build sustainable social systems. She currently serves as a research leader for the COI-NEXT initiative on circular societies using polysaccharide-based bioplastics derived from renewable plants.

Kochi holds a master’s degree in environmental science from Duke University and a Ph.D. in economics from Georgia State University. Her expertise lies in environmental economics, educational engineering, and cognitive science. Her research focuses on transforming values, awareness, and behavior to build sustainable social systems. She currently serves as a research leader for the COI-NEXT initiative on circular societies using polysaccharide-based bioplastics derived from renewable plants.

Yu Kato (Harch Inc. CEO) / Panelists

Yu Kato founded Harch Inc. in 2015. He oversees several digital media platforms focused on sustainability, including “IDEAS FOR GOOD,” “Circular Economy Hub,” and others. Kato also collaborates with businesses, municipalities, and educational institutions to promote sustainability and the circular economy. In April 2023, Harch Inc. earned B Corp certification. He completed the Sustainable Marketing, Media and Creative program at the University of Cambridge Institute for Sustainability Leadership and is a graduate of the University of Tokyo’s Faculty of Education.

Yu Kato founded Harch Inc. in 2015. He oversees several digital media platforms focused on sustainability, including “IDEAS FOR GOOD,” “Circular Economy Hub,” and others. Kato also collaborates with businesses, municipalities, and educational institutions to promote sustainability and the circular economy. In April 2023, Harch Inc. earned B Corp certification. He completed the Sustainable Marketing, Media and Creative program at the University of Cambridge Institute for Sustainability Leadership and is a graduate of the University of Tokyo’s Faculty of Education.

Guest Talks

Radical Circular Design for a Desirable Future Transition (Daijirō Mizuno)

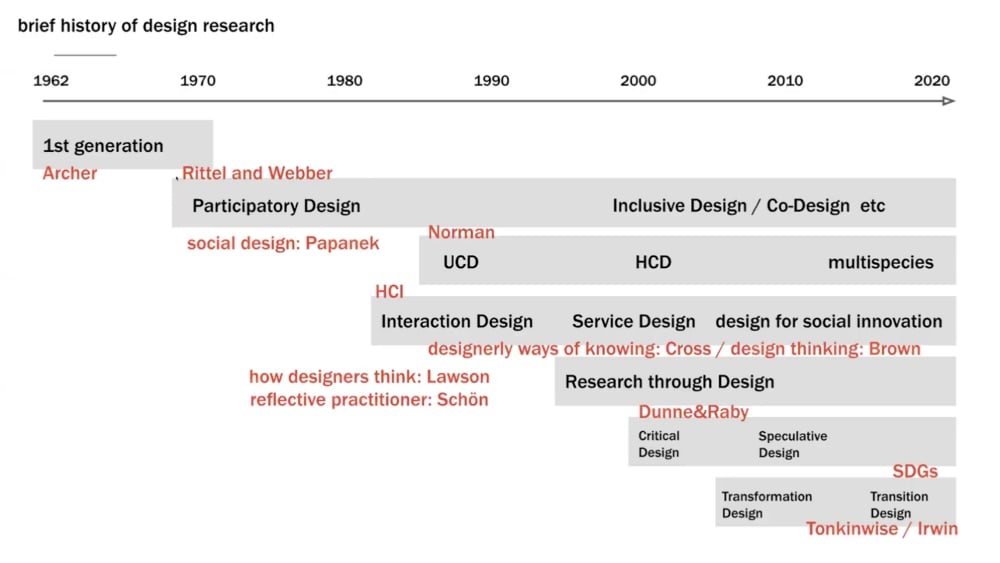

The first speaker was Professor Daijirō Mizuno from Kyoto Institute of Technology, who has long been engaged in research and practice in the field of circular design. He began his talk with a slide that provided an overview of the “history of design,” explaining how design has engaged with solving social issues and creating value.

Slide from the presentation by Mizuno

Mizuno remarked, “Conventional design has been based on the assumption that ‘users = consumers.’ However, today’s issues extend beyond humans to animals, microorganisms, and entire ecosystems. This is why we must reexamine the question, ‘Who is the user?’ If we don’t broaden our design perspective to include diverse agents, we won’t be able to tackle the complex environmental and social challenges we face.”

He also addressed “design thinking,” a major component of contemporary design, emphasizing that it is merely one methodology, and that it is essential to reconsider the values and visions of the future that underlie it.

Mizuno continued, “We live in a time when even humans find it difficult to reach consensus. Precisely because of this, we must fundamentally reexamine our social systems. Circular design holds the potential to support the transformation of society as a whole.”

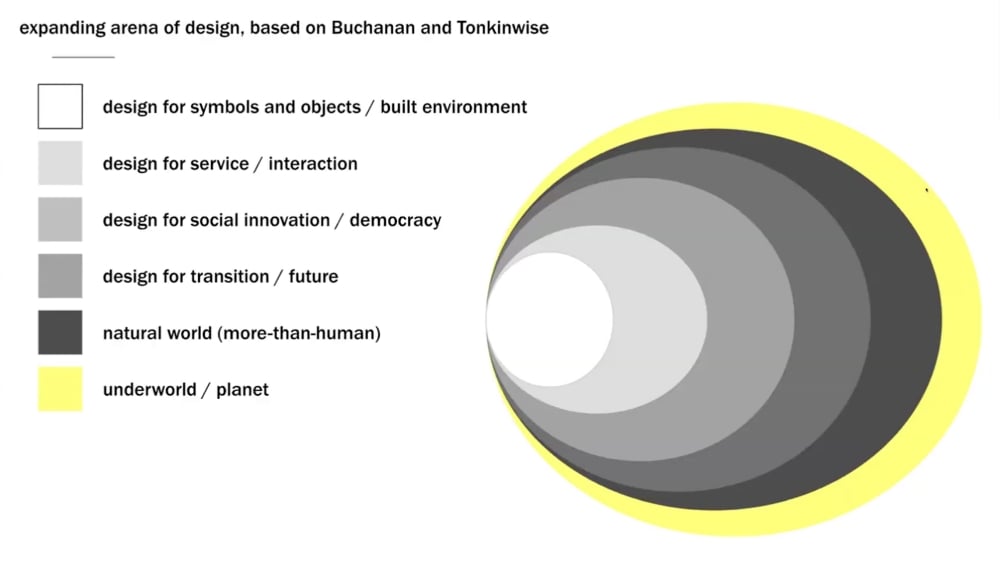

He then introduced a diagram of concentric circles showing the expanding scope of design: from the center—”design for symbols and objects”—to “design for services,” “design for social innovation,” “design for transition,” and eventually extending to “the natural world (beyond humans)” and “the underworld/planetary scale.”

Slide from the presentation by Mizuno

Mizuno explained, “Until now, we have largely ignored the yellow area in this diagram—the ‘underworld.’ But this underworld, which humans have long overlooked, is now surfacing as threats like climate change and wildfires, directly affecting our lives. This situation calls for design that can first and foremost ensure the survival of humans.”

While circular design is often constructed based on systems engineering and controllability, Mizuno emphasized the importance of perspectives that go beyond such control to address emerging challenges. Referring to alternative approaches, such as the Bolivian example introduced in Arturo Escobar’s research, he highlighted the necessity of embracing multiple worldviews that differ from modern Western values.

Mizuno stated, “Participatory design is not only about ‘co-creation’—it is also about ‘struggle.’ Diverse actors must overcome conflict and friction to generate new visions for society. Radical circular design, which we need now, may well emerge from such pluralistic spaces.”

To close his talk, Mizuno introduced the Japanese translation of Arturo Escobar’s book, Designs for the Pluriverse: Radical Interdependence, Autonomy, and the Making of Worlds (in Japanese), for which he served as supervising editor. He highlighted the book’s insights and relevance for achieving radical transformation.

Mizuno concluded, “Escobar urges us to move away from the mindset that resources can be endlessly exploited. He emphasizes the importance of reconnecting with ecosystems and adopting regenerative design. I believe the book offers critical insights for rethinking our ways of living and our worldview at a fundamental level—key to realizing radical circular design.”

Locally Rooted, Circulator-Centered Design and the Technology That Enables It (Hiroya Tanaka)

The second speaker was Professor Hiroya Tanaka from the Faculty of Environment and Information Studies at Keio University SFC. His talk was titled “Locally Rooted, Circulator-Centered Design and the Technology That Enables It.” He began by posing a fundamental question: “What does ‘circulation’ actually mean?”

Tanaka explained, “The Latin root of ‘circle’ implies the presence of a center. In Japanese, the character ‘環’ (ring or cycle) evokes imagery of spiritual rotation and time-honored, cyclical practices. The English term ‘circulation’ strongly conjures the idea of substances changing states while moving through space. Just like blood or water circulates, many human and natural activities also involve state changes. In Japanese culture, too, we find deeply rooted concepts of ‘circulation,’ as seen in architectural traditions like the periodic rebuilding of the Ise Shrine.”

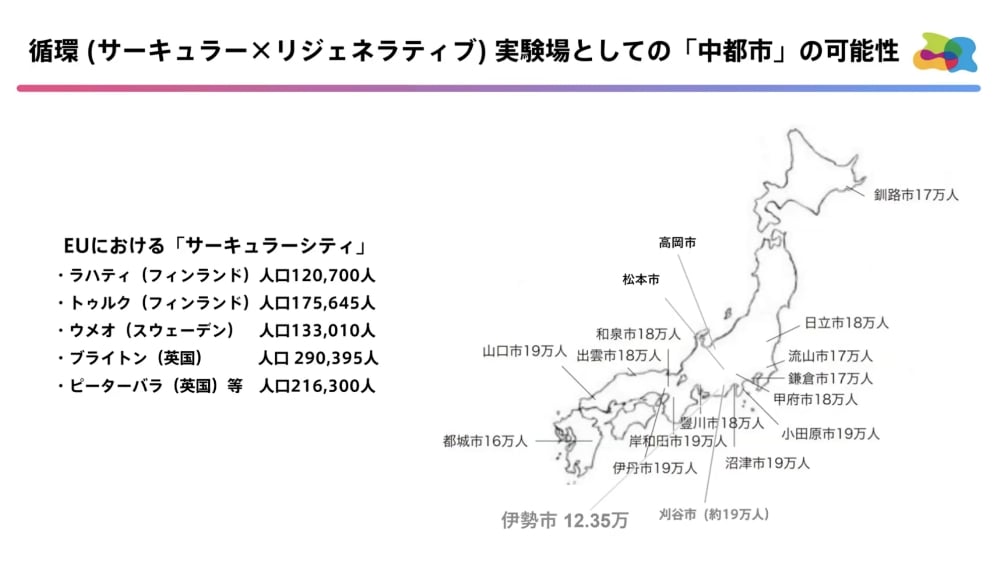

Building on this, he emphasized the importance of drawing on local wisdom and historical practices of resource circulation, and adapting them into sustainable models for today’s economic systems. He also noted that such initiatives may be more practical in mid-sized cities, which are often better suited to reflect regional characteristics.

Designing circulation systems that reflect local characteristics can support not only resource management, but also economic revitalization and community resilience.

Tanaka added, “Mid-sized cities hold great potential as testing grounds for circulation. In Europe, cities with populations of around 100,000 to 200,000 are gaining attention as ‘circular cities.’ Japan, too, has many cities of similar scale.”

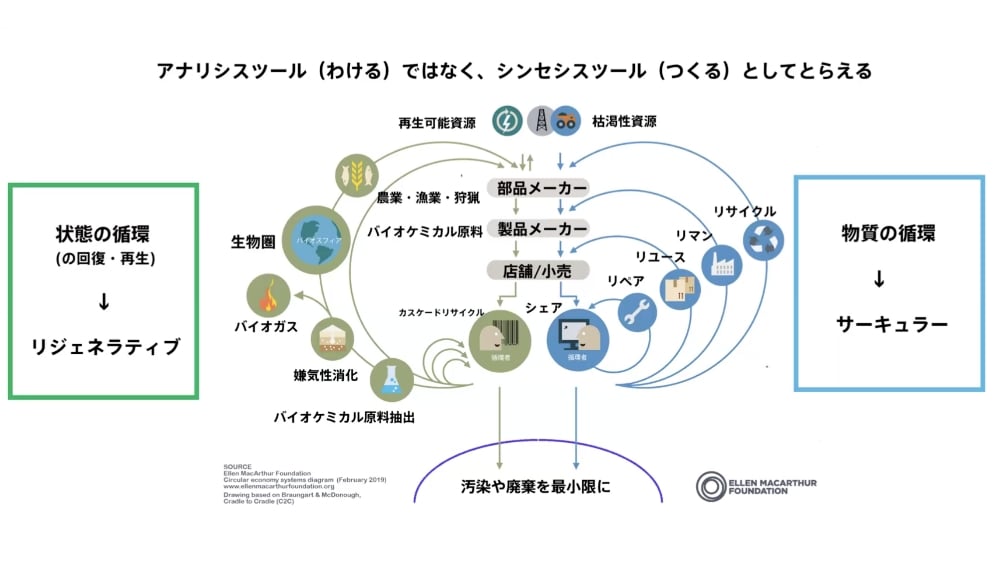

Slide from the presentation by Tanaka

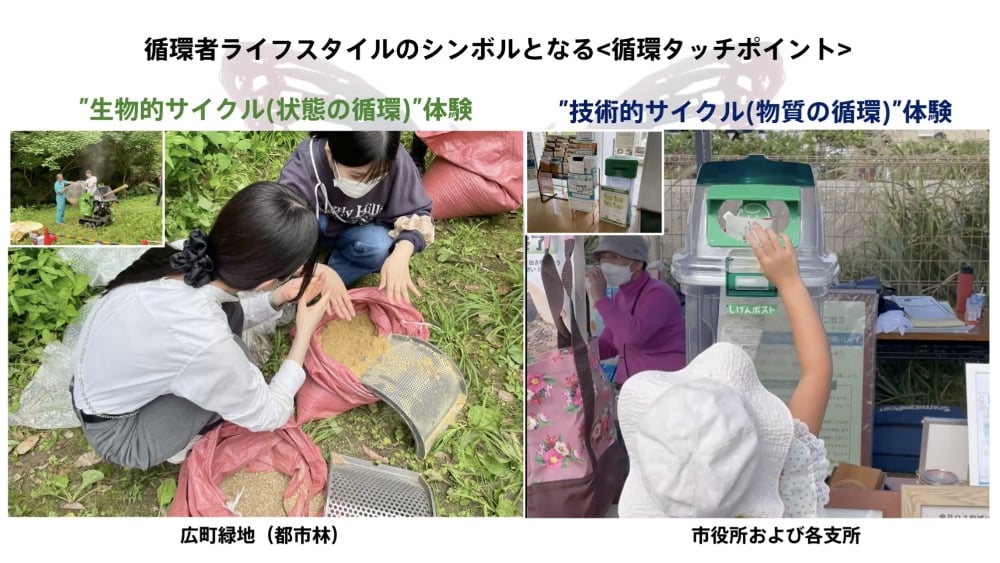

He also referenced the concept of the “15-minute city (in Japanese),” noting that promoting circulation in urban settings requires more than green coverage—it must be on a scale where residents can directly participate. By taking part in local waste collection or recycling efforts, such as those at city halls and branch offices, people gain a sense of self-efficacy.Tanaka refers to these individuals as “circulators.”

Slide from the presentation by Tanaka

Tanaka explained, “When people can experience both the ‘biological cycle’ and the ‘technical cycle’—as illustrated in the butterfly diagram—as a unified system, circulation feels more tangible. It’s important not only to analyze these cycles separately but also to consider them together. In the long term, technologies and architecture must focus on how to increase circulators and create environments where circulation is a lived experience.”

He also highlighted the role of architecture’s time scales. As shown in Stewart Brand’s concept of ‘Pace Layering,’ different elements of a structure or facility have varying update cycles. Architecture, Tanaka suggested, can serve as a medium that temporarily holds and integrates these different temporal layers. For instance, in Kamakura, a project was conducted to design a tea room using local materials.

Slide from the presentation by Tanaka

These efforts aim to transform regions and cities from passive sites of consumption into active hubs of circulation, thereby expanding networks of circulators. Tanaka’s talk provided valuable perspectives on increasing active participation in circular systems, grounded in Japan’s own culture of circulation, and its relationship with technology and architecture.”

Transforming Consumer Values and Bringing Happiness through Systemic Design (Ikuho Kochi)

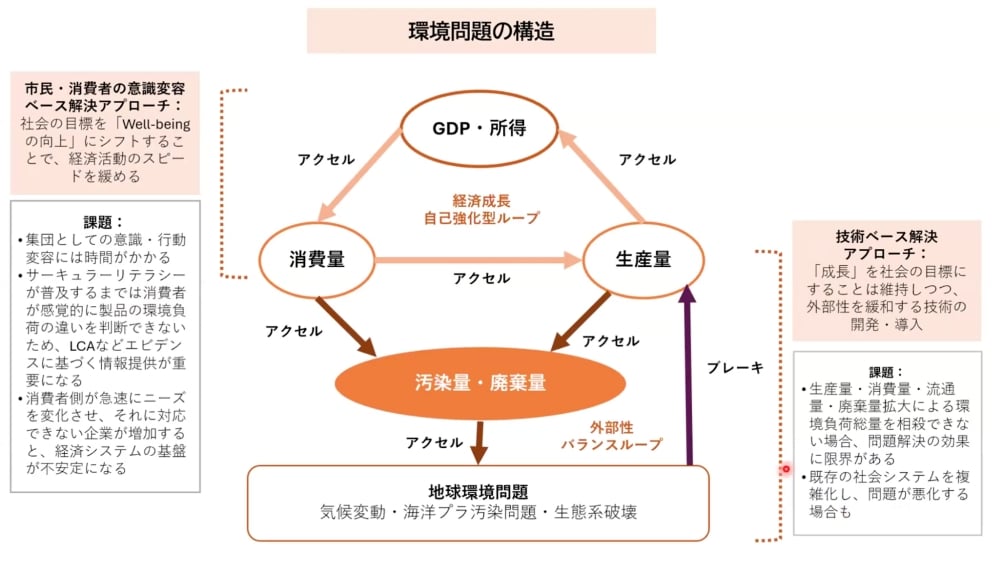

The final speaker was Ikuho Kochi from the Institute of Science and Engineering, Kanazawa University. Specializing in environmental economics, educational engineering, and cognitive science, Kochi works on transforming various social systems, including circular business. She began by pointing out how the existing frameworks have become insufficient in slowing the worsening of global environmental issues.

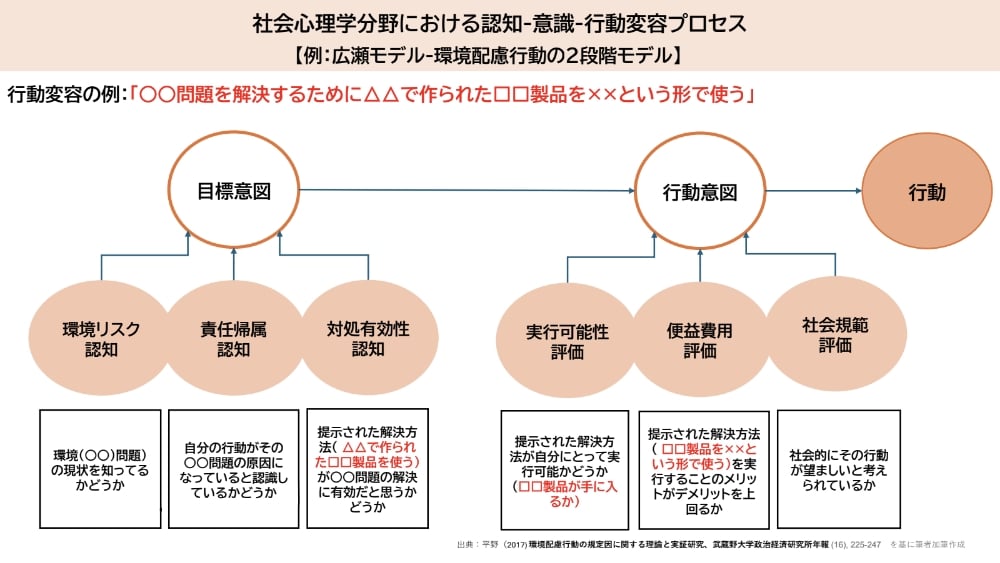

Kochi explained, “To accelerate decarbonization, we must reevaluate the entire structure of society through a systems-thinking lens, such as the one exemplified by the Limits to Growth model. There are two broad solution approaches to reducing environmental impact: one based on transforming individual awareness (where citizens and consumers voluntarily change their behavior), and the other based on technology (introducing innovative technologies and new business models). However, both approaches have challenges. Even if technology solves a problem, it’s unclear whether it truly offsets the total environmental burden.”

Slide from the presentation by Kochi

Kochi continued, “The pricing of low-environmental-impact products is also a key issue. For example, if measures like a carbon tax are introduced to make companies bear the environmental costs, this could lead to price hikes, shifting the burden to consumers. It’s important to coordinate society as a whole, starting from awareness transformation on the demand side (consumers), then moving toward the supply side (companies).”

According to Kochi, this requires a shift toward lifestyles that do not promote excessive consumption. For example, quantitatively and qualitatively evaluating the social impact of circular businesses and creating alternative products and services that people ‘want’ to choose is essential. A comprehensive design that includes not only pricing mechanisms but also lifestyle images is needed.

Kochi emphasized, “Transforming the linear consumption structure requires mechanisms that actively engage citizens and consumers in their everyday lives—not just companies and governments. It’s crucial to design a process that connects awareness and cognition to concrete action and ensures it continues.”

Slide from the presentation by Kochi

With these perspectives in mind, Kochi introduced a framework called “systemic design” to support individuals in living sustainably while increasing their well-being. Her approach emphasizes that both awareness transformation and technological implementation are vital in rethinking society and the economy at large. In addition to advancing the circular economy, transforming consumer values and designing systems that foster well-being are essential.

Panel Discussion: “Transitions Toward a Circular Future”

In the latter half of the session, a panel discussion was held under the theme of “Transitions Toward a Circular Future,” moderated by Yu Kato, CEO of Harch Inc. The central question posed was: “Can care and feminist perspectives be integrated into the startup model?”

Startups are expected to continuously drive innovation to address increasingly complex environmental and social challenges, including climate change and resource scarcity. However, typical startup culture—characterized by rapid growth fueled by investment and a strong emphasis on efficiency and speed—has often been linked to patriarchal tendencies. In this context, is it possible to reframe business activities and organizational operations through the lens of care and feminism?

Mizuno:

“I think startup culture has always had a kind of ‘macho’ mindset. The question is how we can incorporate care and altruism into that. If more startups are driven by the motivation of ‘doing it because it’s fun,’ I believe we’ll see businesses emerge that differ from those powered by brute-force patriarchal approaches. There are movements in Europe that adopt bioregional and terroir perspectives, thinking holistically rather than just ‘developing’ regions.”

Tanaka:

“I find it interesting that startups are positioned between producers and consumers. For instance, household tasks like cleaning or bathing — traditionally viewed as either public or private — are essential to society. Positioned between large corporations and individual consumers, startups are uniquely placed to offer new approaches to societal challenges.”

Kochi:

“In the circular economy workshops I participate in, we often have many housewives attending. Perhaps because of their strong concern for the next generation, they tend to shift their thinking from linear to circular very quickly. Private communities for exchanging children’s used clothing already exist among these individuals, but when companies step in, there’s a risk that such communities might collapse.”

Tanaka pointed out that startups, unlike large corporations, can maintain a close connection with communities while also being recognized as businesses. However, as startups grow, maintaining close ties with local communities becomes increasingly difficult. Mizuno cited examples of companies that ended up disrupting local systems.

Tanaka:

“We need to rethink the investment structure itself. If banks could provide loans to startups that prioritize slow growth while valuing local communities, it would create incentives for businesses that incorporate feminist and care-oriented perspectives.”

Scenes from the event

Conclusion

This special academic session explored what is needed to realize a circular economy from three perspectives: design, technology, and lifestyle. Mizuno emphasized the importance of questioning existing values through radical circular design and the concept of pluriverses. Tanaka discussed the role of technology and architecture in fostering “circulators” rooted in local communities. Kochi introduced a systemic approach that focuses on transforming consumer awareness and encouraging sustainable behavior.

Through the discussions, it became clear that advancing the circular economy requires not just technological innovation, but also collaboration with communities and the integration of diverse perspectives in design. Expectations are rising for entrepreneurs and startups participating in CIRCULAR STARTUP TOKYO to leverage these insights in developing their businesses further.